En linux. portable perso:

lscpu

Architecture : x86_64

Mode(s) opératoire(s) des processeurs : 32-bit, 64-bit

Address sizes: 39 bits physical, 48 bits virtual

Boutisme : Little Endian

Processeur(s) : 2

Liste de processeur(s) en ligne : 0,1

Identifiant constructeur : GenuineIntel

Nom de modèle : Intel(R) Celeron(R) N4020 CPU @ 1.10

GHz

Famille de processeur : 6

Modèle : 122

Thread(s) par cœur : 1

Cœur(s) par socket : 2

Socket(s) : 1

Révision : 8

Vitesse maximale du processeur en MHz : 2800,0000

Vitesse minimale du processeur en MHz : 800,0000

Caches (sum of all):

L1d: 48 KiB (2 instances)

L1i: 64 KiB (2 instances)

L2: 4 MiB (1 instance)

NUMA:

Nœud(s) NUMA : 1

Nœud NUMA 0 de processeur(s) : 0,1

Moore’s law, which said, depending on who you believe, that either the number of transistors or the speed of processors would double every 18 months… until ’90.

Data Representation

CPU Architecture

Switches

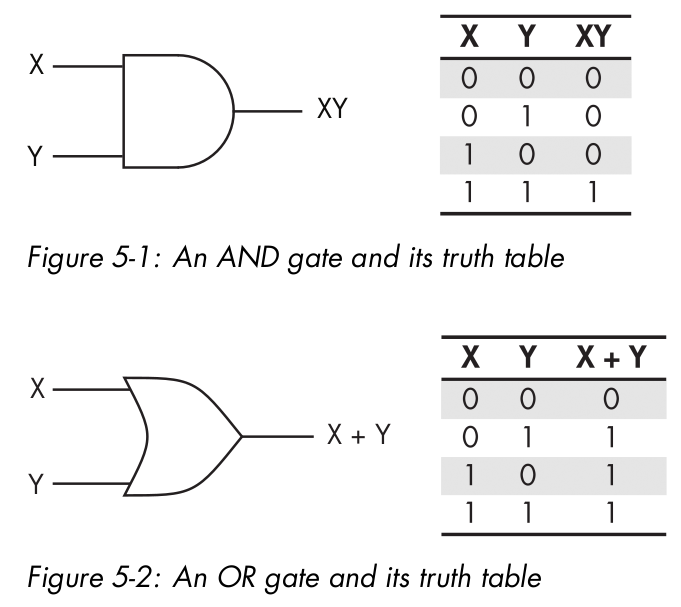

Digital Logic: Claude Shannon, 1936

Simple Machines

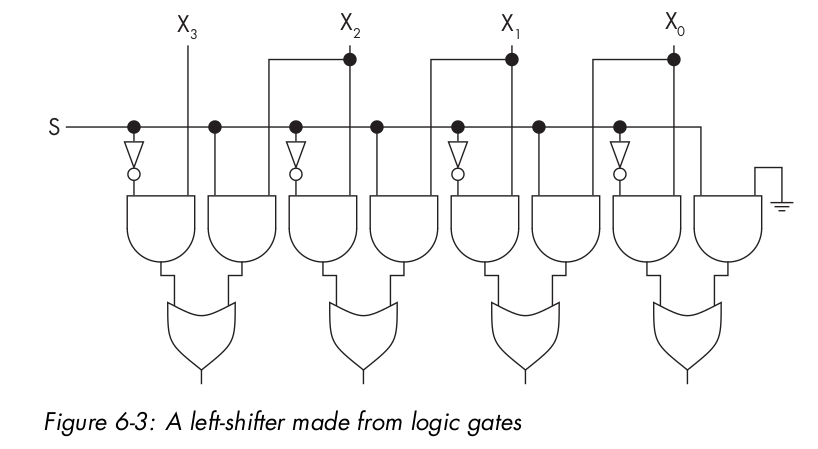

Shifters

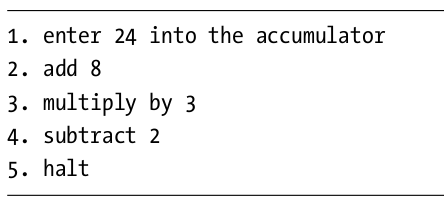

In base 10, there’s a fast trick for multiplying integers by 10: just append a zero to the end. We can also multiply by a higher natural power of 10, 10n , by appending n zeros. Rather than thinking of it as appending a zero, think of it as shifting each digit one place to the left. Then the trick also works

for multiplying non-integer numbers by powers of 10. We can similarly do easy and fast divides by powers of 10 by shifting the digits to the right.

Digital CPU Design

01: HLT

The HLT instruction stops the CPU from getting to address 2 and beyond, preventing the data values from

being treated as instructions.

Constantes:

01: HLT

02: NUM 10

03: NUM 5

04: NUM 0

Load and Store

01: LDN 20

02: STO 21

03: HLT

20: NUM -10

21: NUM 0

Arithmetic

the following program computes 10 – 3 = 7:

01: LDN 20

02: SUB 21

03: STO 22

04: LDN 22

05: HLT

20: NUM -10

21: NUM 3

22: NUM 0

Jumps

01: LDN 20

02: SUB 21

03: SUB 22

04: STO 20

05: JMP 23

06: HLT

20: NUM 0

21: NUM 0

22: NUM -1

23: NUM 0

Branches

Branching in the Baby is performed by the SKN instruction (skip next).

This program computes the absolute value of an integer input from address 20 and stores the result in address 23. That is, if the input is either –10 or 10, then the output will be 10; any negative sign is removed. Lines 03 and 0.4 are the SKN-JMP pair.

01: LDN 20

02: STO 23

03: SKN

04: JMP 21

05: LDN 22

06: SUB 23

07: STO 23

08: HLT

20: NUM -10

21: NUM 6

22: NUM 0

23: NUM 0

Registers

Input/Output

Memory

Random access means that any random location in memory can be chosen and accessed quickly, without some regions being faster to access than others.

Because SRAM is made from flip-flops (the same structures that are used to make CPU registers), it’s fast and expensive.

Dynamic RAM (DRAM) is cheaper and more compact than SRAM, but slower. Instead of being made from flip-flops, it’s made using cheaper and slower capacitors. A capacitor is a component for storing electric charge.

Read-only memory (ROM) traditionally refers to memory chips that can only be read from, not written to, and that are pre-programmed with permanent collections of subroutines by their manufacturer, then mounted at fixed addresses in primary memory.

Erasable programmable ROM (EPROM) is like PROM, but the chip’s data can be erased using ultraviolet light. Then new data can be burned on. This cycle can be repeated many times.

Flash memory is EEPROM that can be erased and rewritten block-wise, meaning you can selectively wipe and rewrite just one small part, or block, of the memory at a time.

A cache is an extra layer in the memory pyramid between the fast registers of the CPU and the slower RAM. It stores copies of the most heavily used memory contents, making them available for quick retrieval.

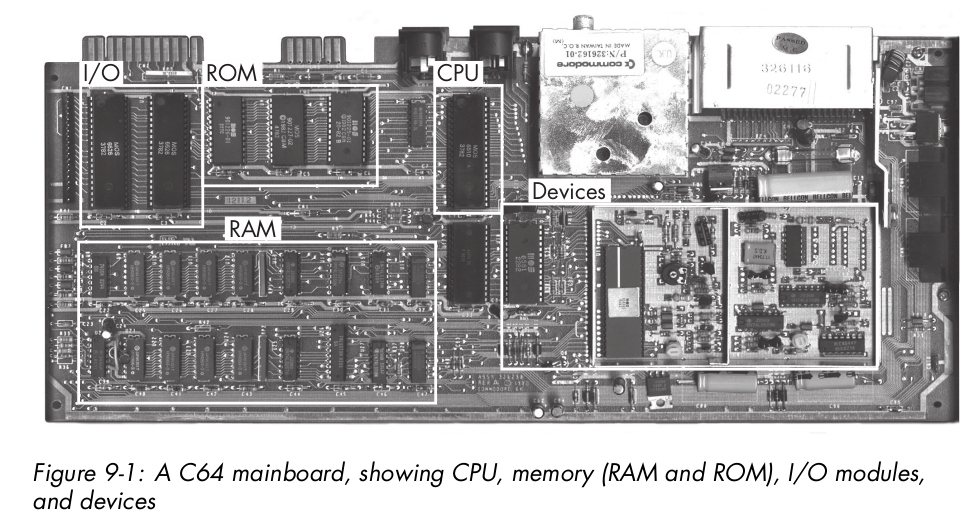

Retro Architecture

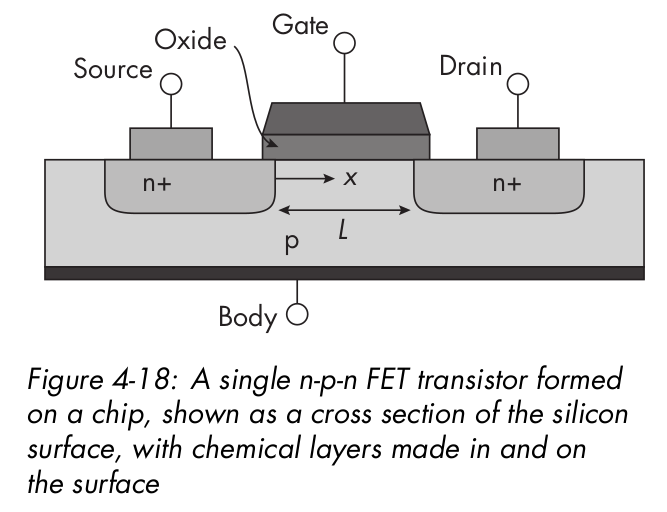

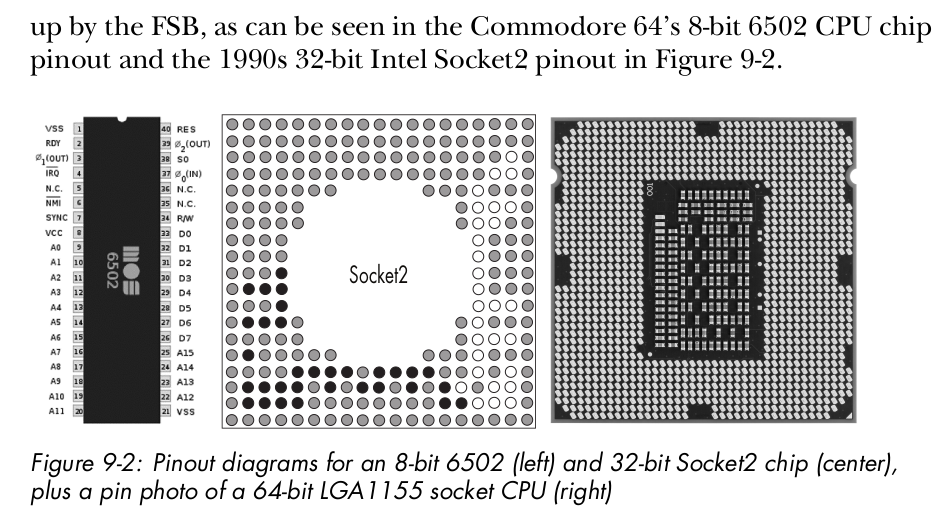

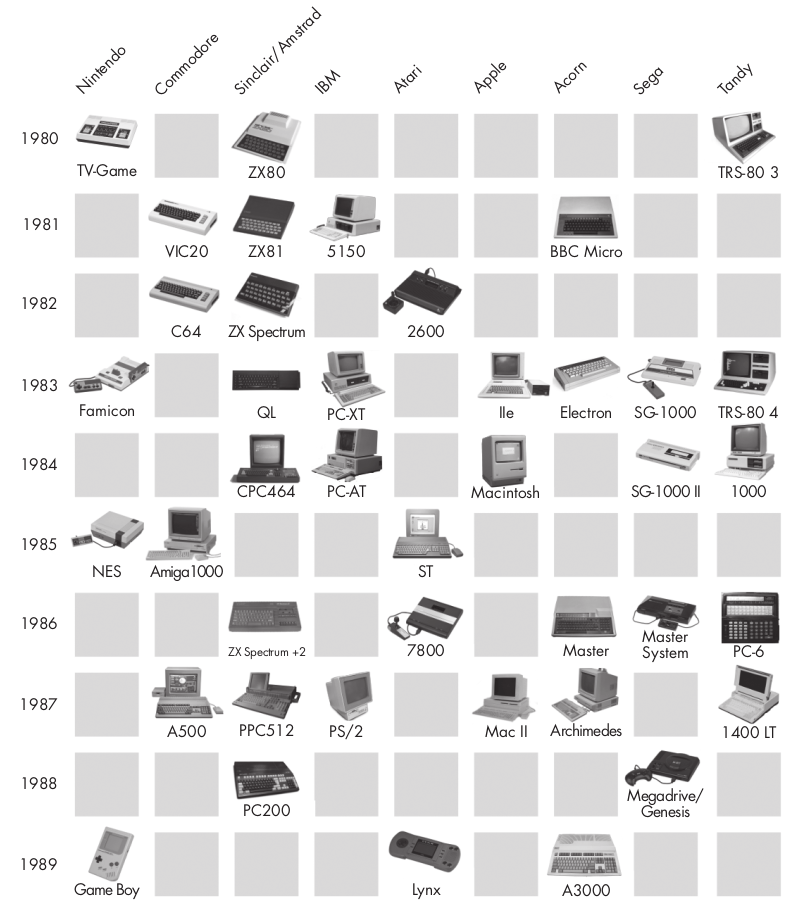

MOS Technology’s MOS 6502 was an 8-bit processor, designed in 1975 by Chuck Peddle. MOS stands for metal-oxide semiconductor, as in the MOS field-effect transistors, or MOSFETs, used by the company. The 6502 was used in many of the classic 8-bit micros of the 1980s: the Commodore 64, NES, Atari 2600, Apple II, and BBC Micro

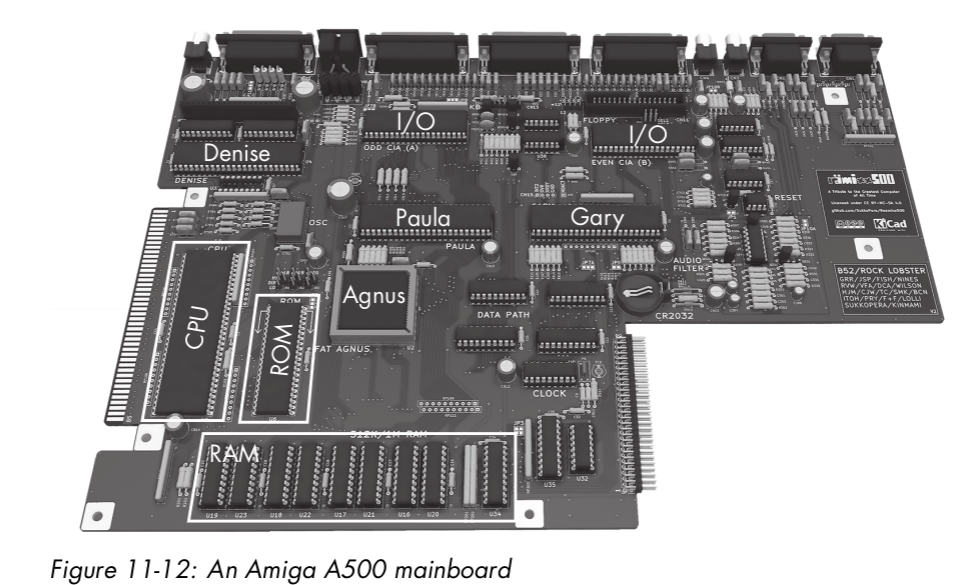

Agnus This chip contained a coprocessor (“copper”) with its own separate RAM and bus, in addition to the main CPU system. The copper was responsible for graphics. Machine code for the copper could be written as data lines and sent to the copper as data by the main CPU program. (A similar system is used today in GPUs.) Agnus also contained a DMA-based “blitter,” used for copying sprites onto video RAM without CPU.

Paula This chip contained a sound device and its I/O module, as well as several other I/O modules, such as for disks and communications ports. It used DMA to read audio samples and other I/O data from

RAM without CPU intervention.

Denise This was the VDU chip, reading sprites and bitplanes from RAM, compositing them together under various screen modes, and out- putting CRT display controls.

Gary This was a memory controller, translating and routing addresses from the bus to particular chips and addresses within them.

Retro mouse

Keyboards in the retro age were typically memory-mapped, with each key wired directly to an address in memory space to look like RAM. There would be a group of addresses together, each mapped to a key, and by loading from one you could determine if the key was up or down.

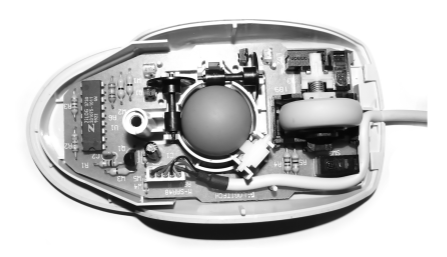

Mice work by physically rolling a thumb- sized rubber ball over your desk, which in turn spins two roller sensors detecting its horizontal and vertical rotations. The sensors convert the rotations into analog then digital signals to send down the wire to your computer.

Serial Port:

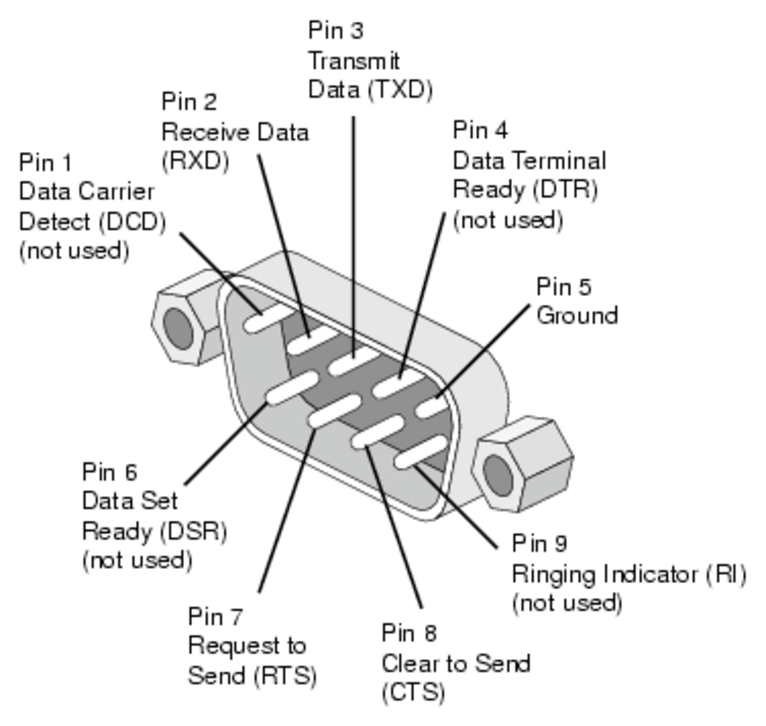

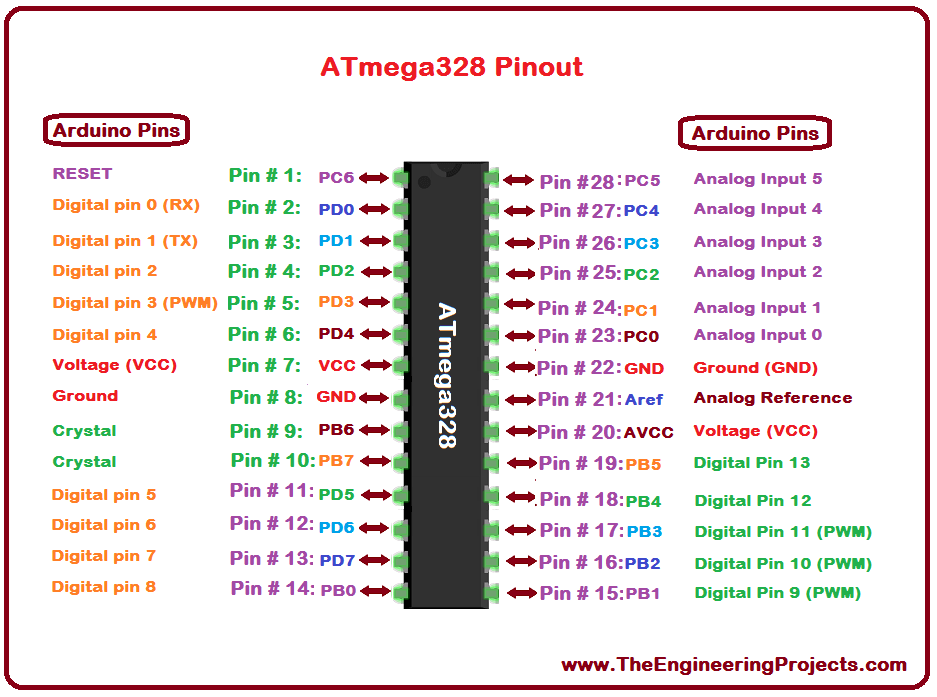

The serial port was, and still is, a simple communications protocol (formally the RS232 standard) found on retro machines but still very relevant in embedded systems today. The core of a serial port is two wires, called RX and TX, which stand for receive and transmit, respectively. These use digital voltages over time to transmit 0s and 1s, so there’s one wire sending information one way and another wire sending information the other way. A historical serial port has many other wires as well, as in the old days they were used as controls for many things, but nowadays we tend to use only RX and TX.

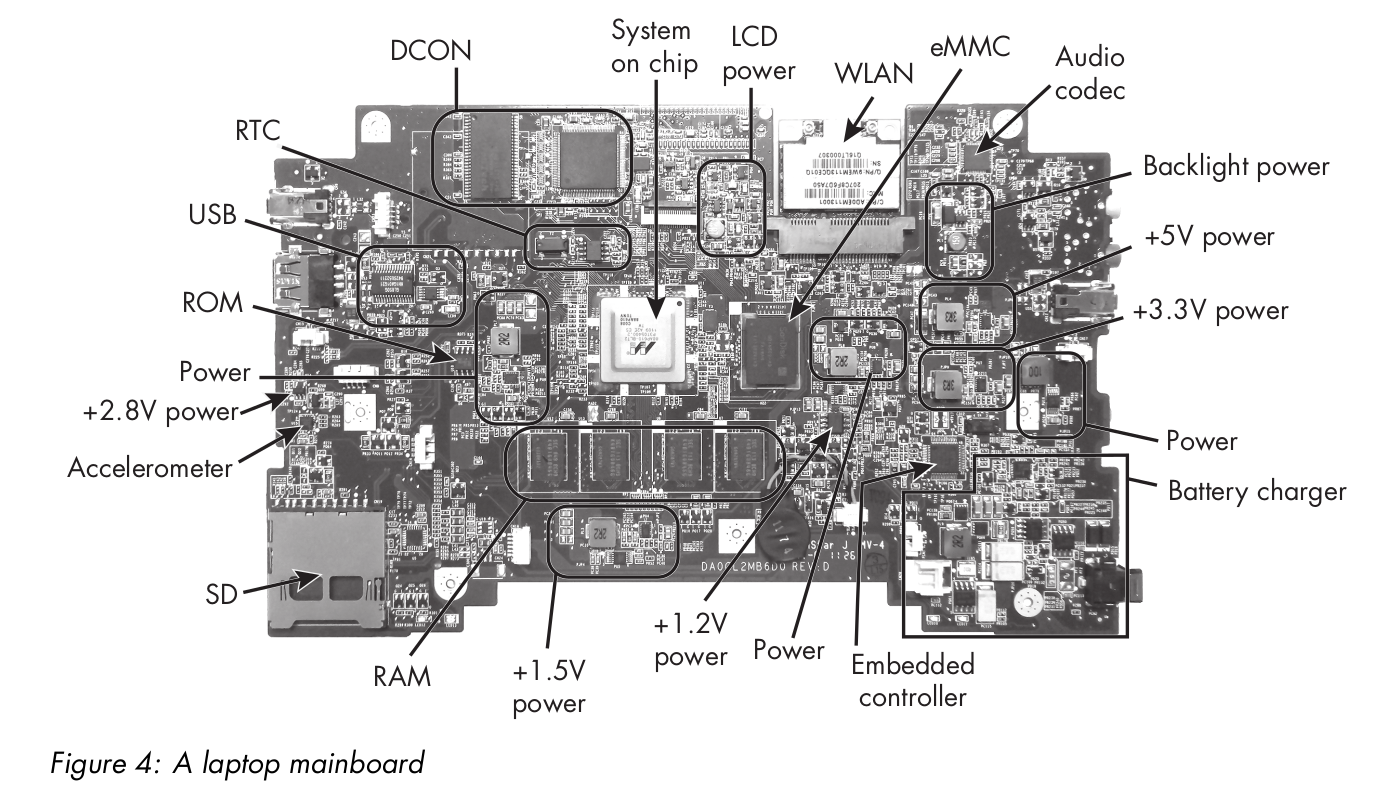

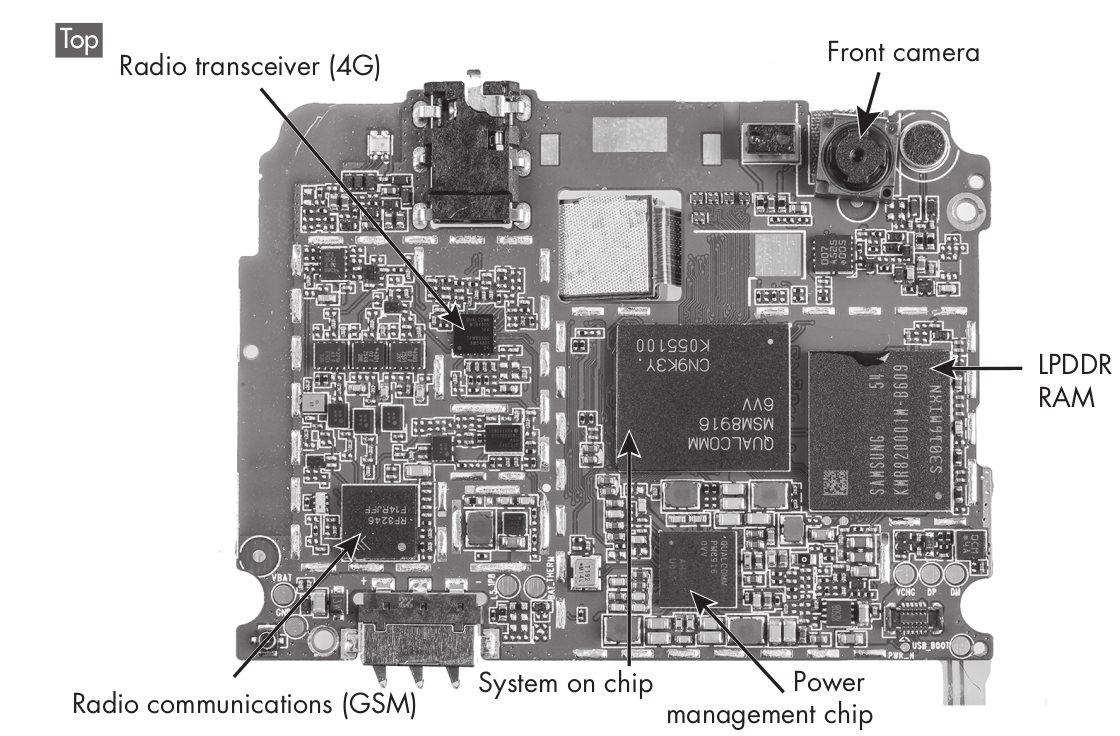

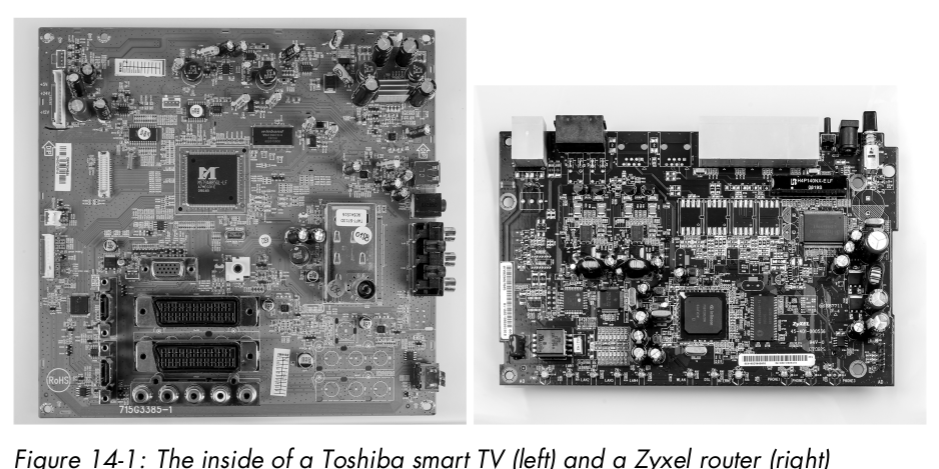

Architecture intégrée

A microcontroller (aka a microcontroller unit, MCU, or μC) is a chip including a CPU that’s designed and marketed for embedded applications.

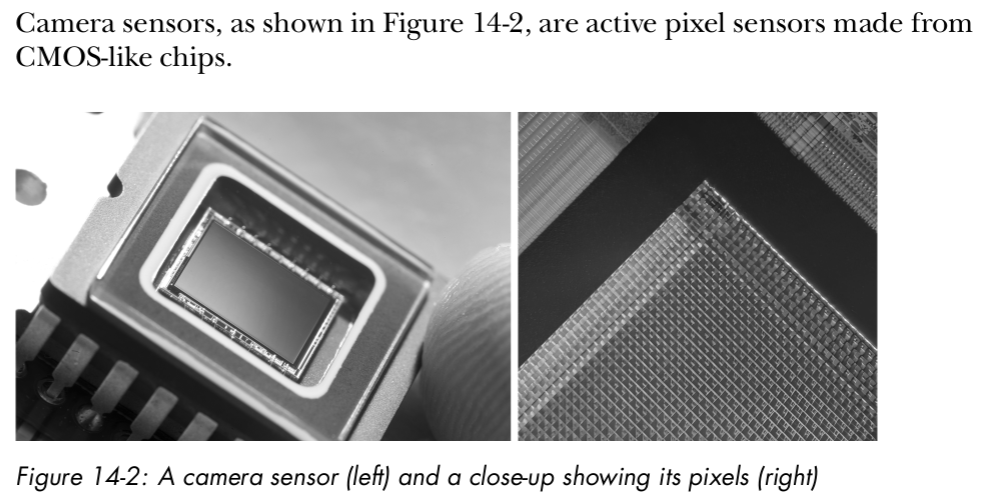

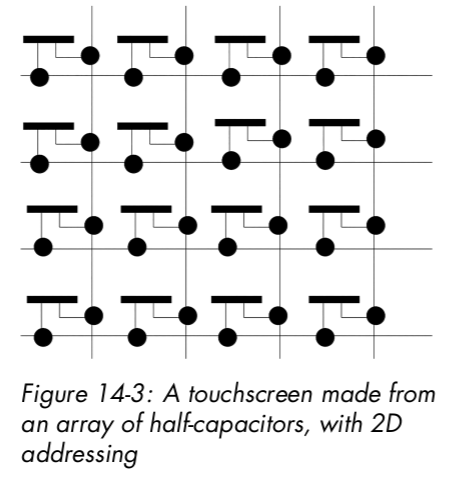

Entrées/Sorties intégrées

The Inter-Integrated Circuit bus, pronounced “eye-two-see” (written as I2 C and sometimes pronounced “eye-squared-see”), is a standard for connecting chips together. It’s very common in robotics.

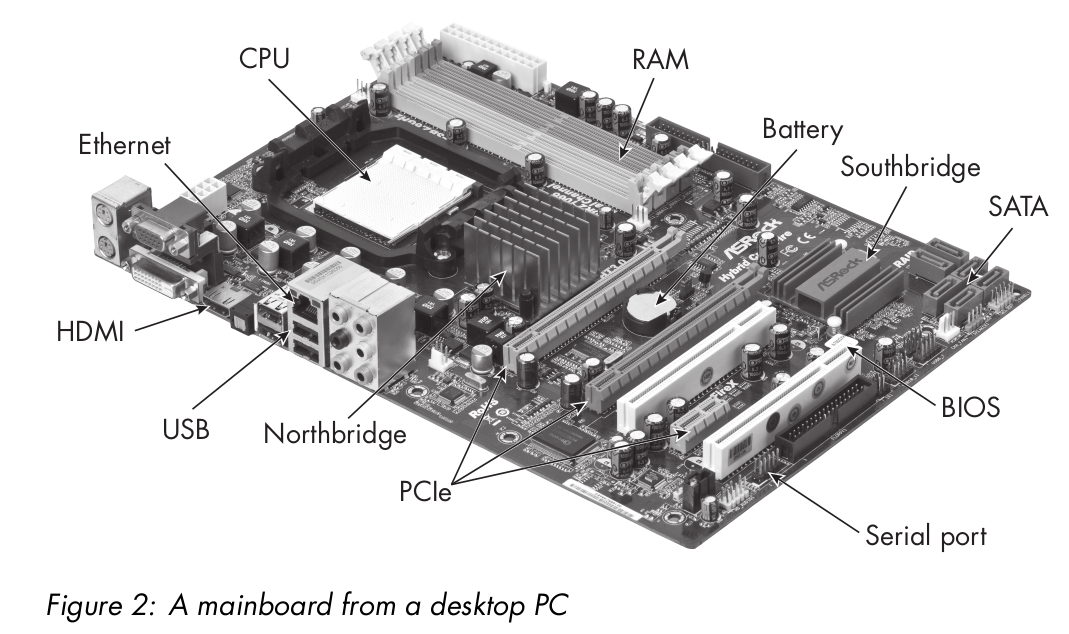

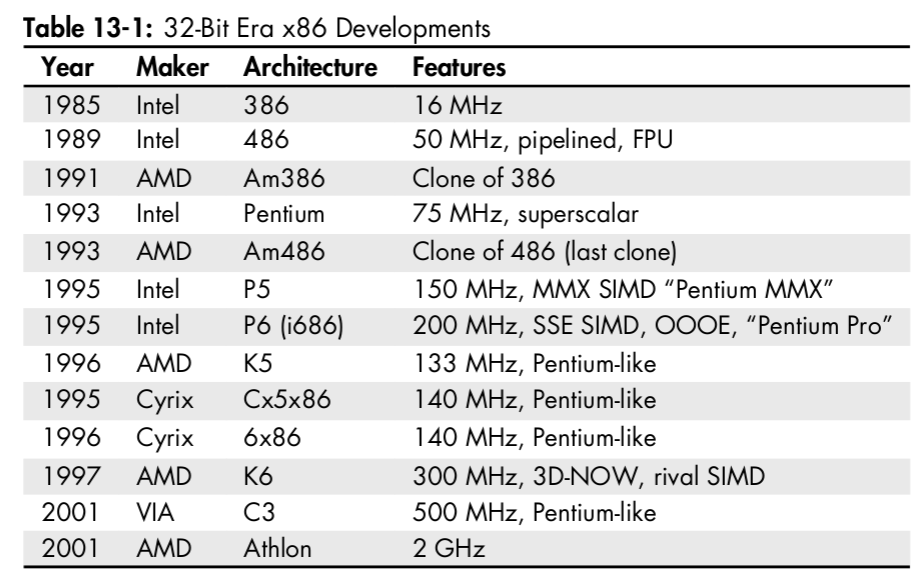

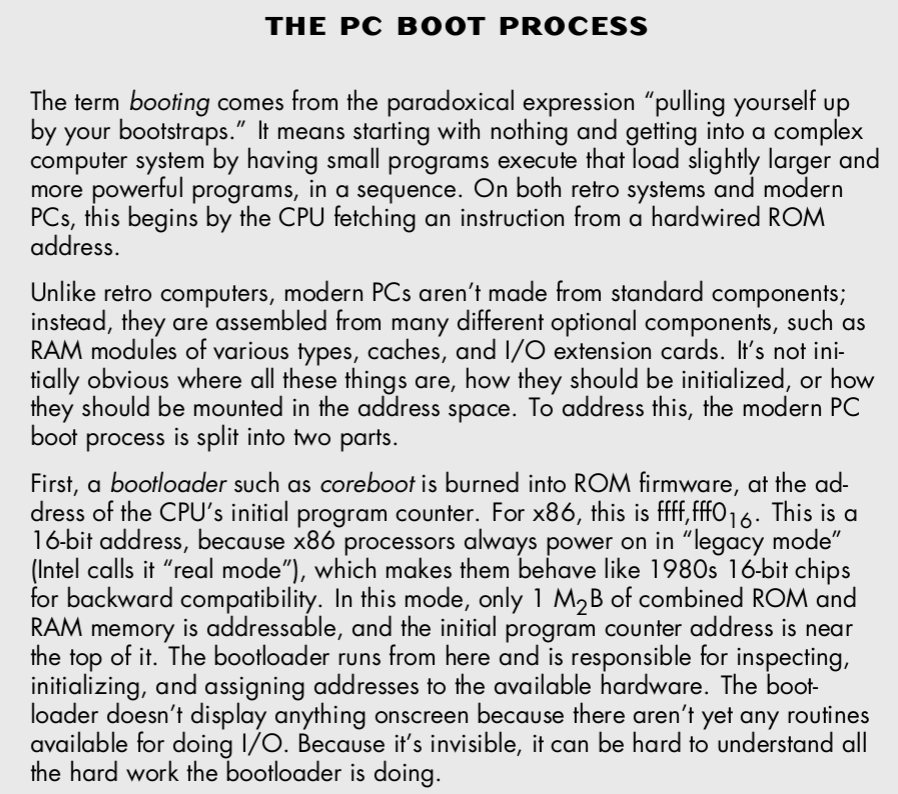

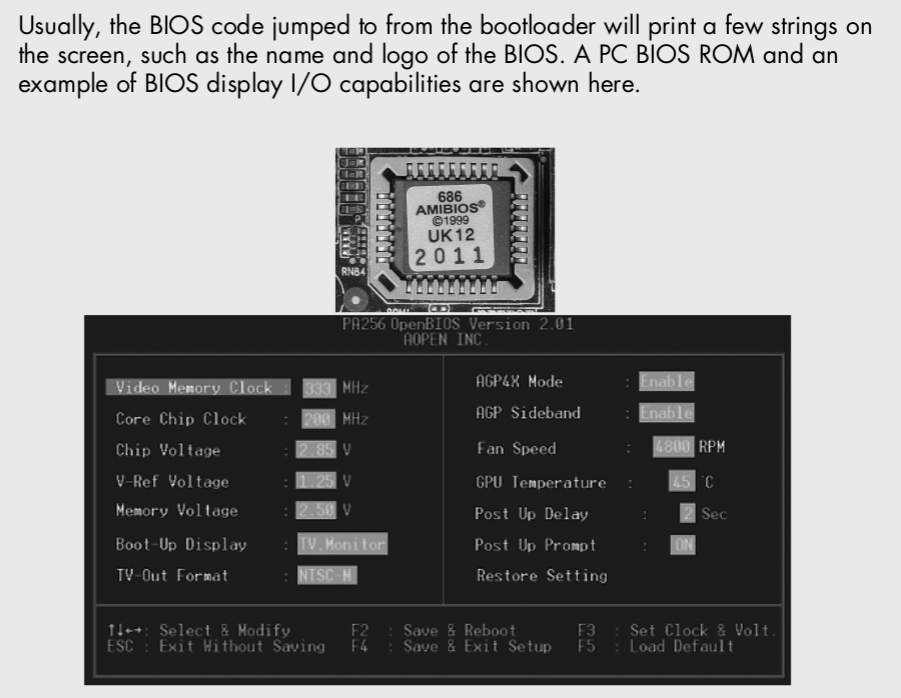

Desktop Architecture

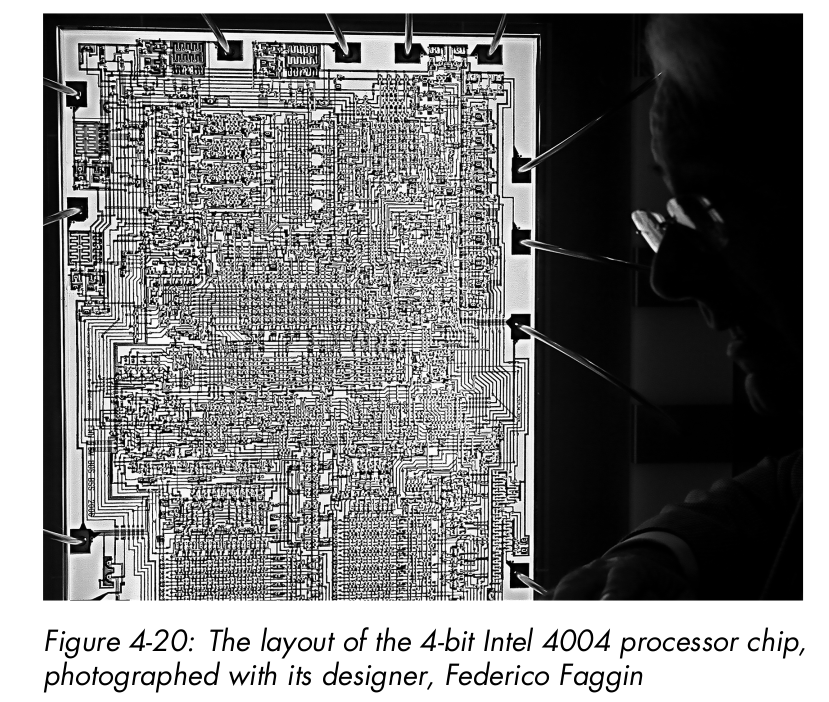

The first member of the x86 family proper—defined by modern backward compatibility—was Intel’s 16-bit, 5 MHz 8086 chip, made in 1978. This was a CISC chip that used microprogramming. x86 is named after its last two digits.

Competition between Intel and AMD became formalized in 1982 by a three-way contract between Intel, AMD, and IBM, whose business at the time was building computers. IBM wanted to buy CPUs for its computers but didn’t want to be locked into using a proprietary design from a single company, because such a company could then hold IBM to ransom via the lock-in and increase its prices.

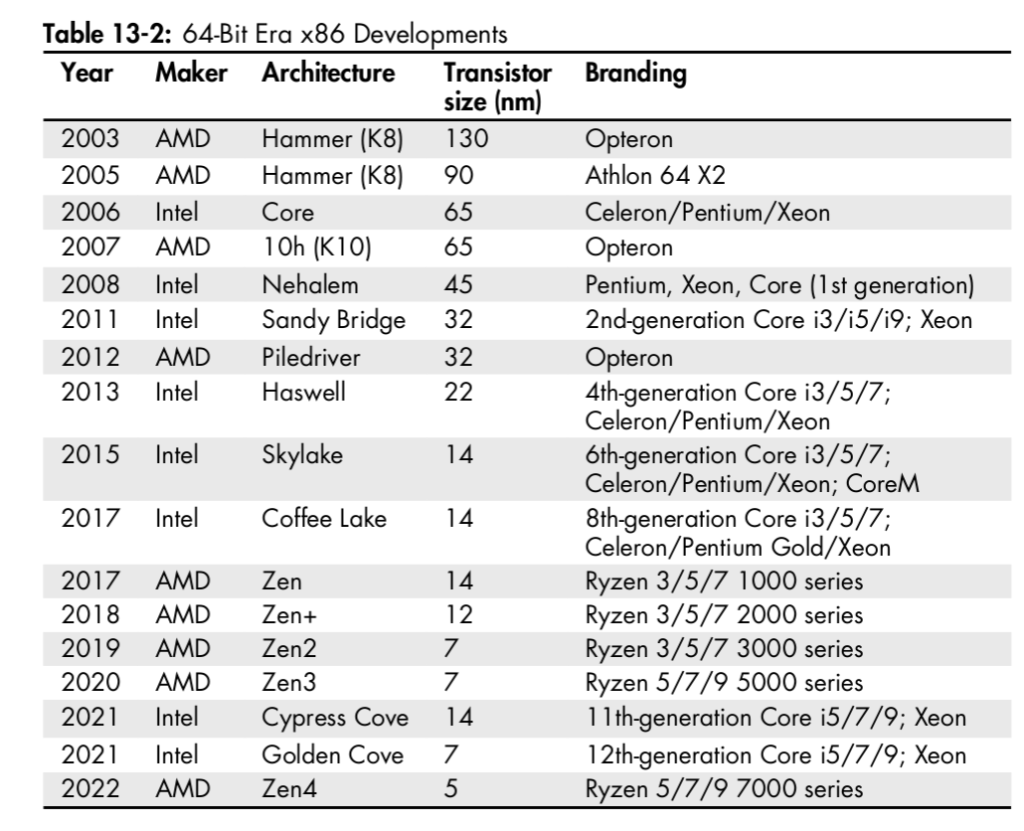

The 64-bit era is characterized by a separation of marketing terms from the underlying technologies, with the same marketing brand often used to label completely different architectures. Unlike the previous 32-bit Pentium, the branding is no longer attached to specific designs. You’re probably used to seeing 64-bit products with brands like Pentium, Celeron, and Xeon. You may also see the numbers 3, 5, 7, and 9 in brand names, as in Core i3, Core i5, and so on. For Intel, these numbers don’t mean anything other than suggesting an ordering of which products are better; AMD uses the same numbers to suggest which products are similar to Intel’s.

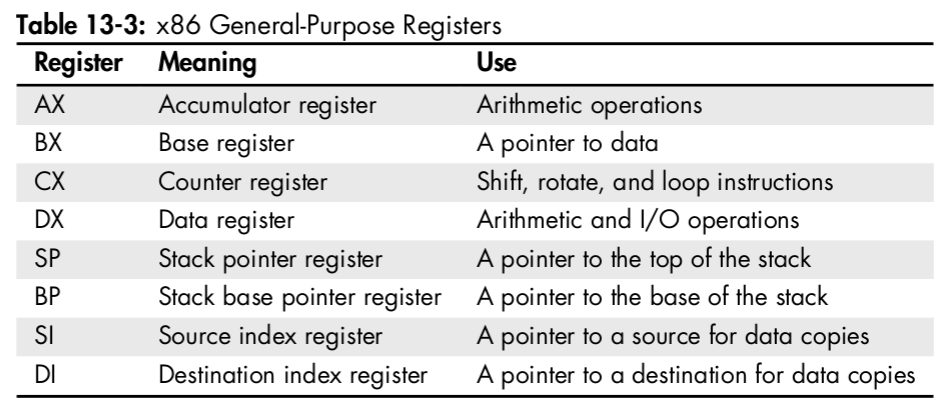

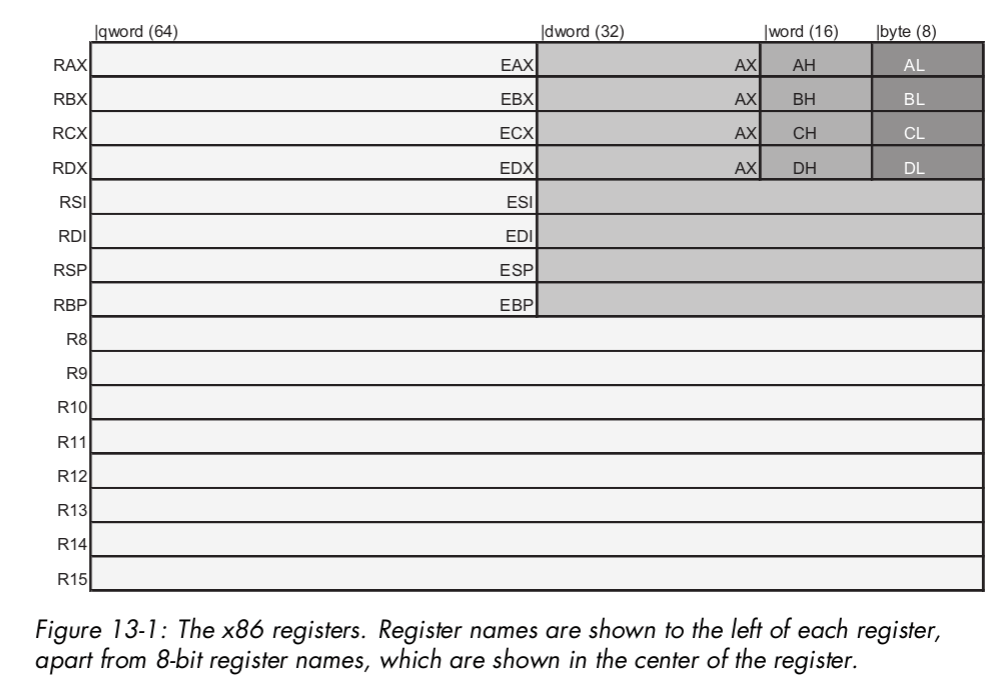

In the original 16-bit 8086, the general-purpose registers all had 16 bits. To retain partial backward compatibility with the previous 8-bit 8080, the first four—AX, BX, CX, and DX—can also be split into two 8-bit registers, named with H and L for high and low bytes, which can be accessed independently.

IA-32 extended the eight registers to have 32-bits. They can still be accessed as 16- or 8-bit registers as before, to maintain compatibility. To access them in their full 32-bit mode, we add the prefix E (for extended) to their names: EAX, EBX, ECX, and so on.

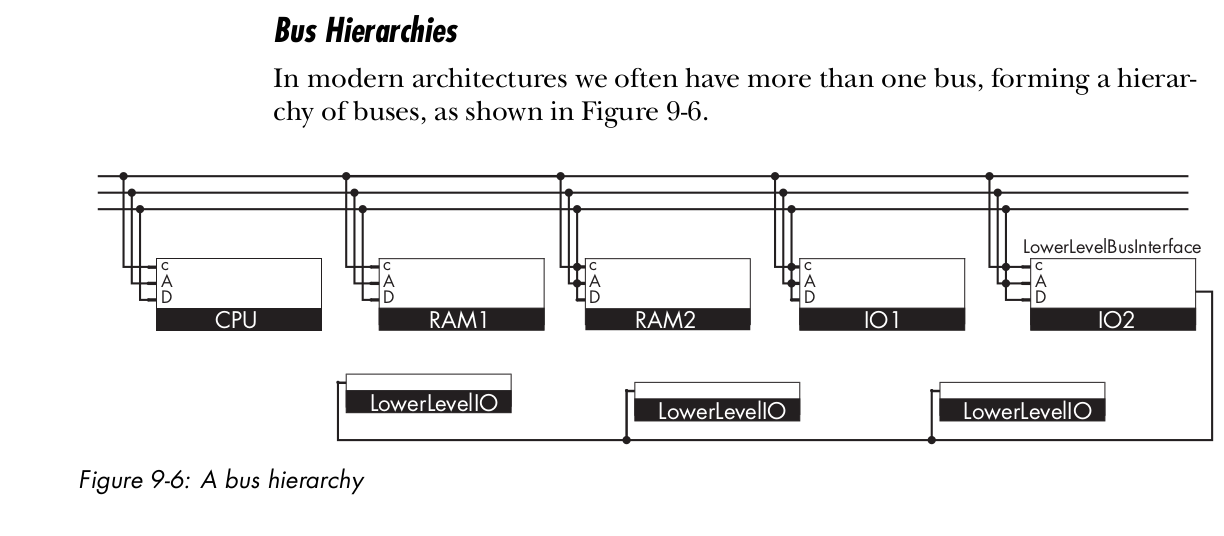

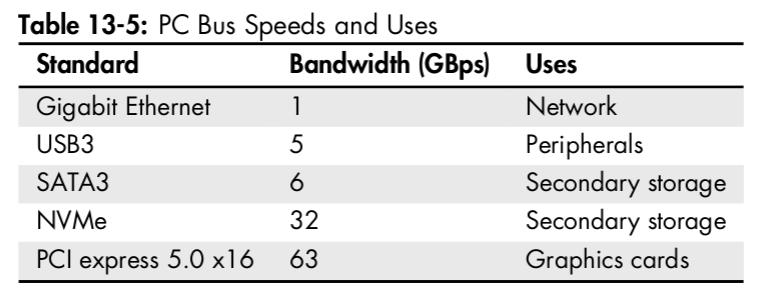

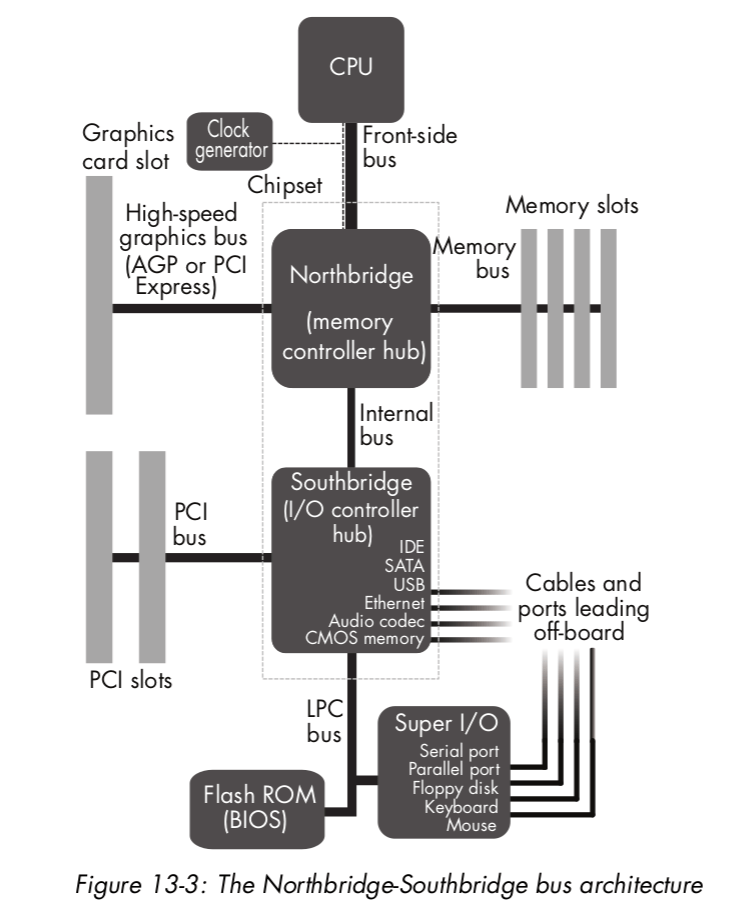

Buses can be found in a desktop PC at several layers; each layer has different uses and different bandwidths, and is optimized for different purposes

Northbridge connects directly to the CPU’s FSB (front-side bus) and links it to RAM and to fast I/O modules using the same address space via PCIe bus. It also connects to Southbridge. Northbridge is fast and powerful. It was traditionally constructed on a separate chip from the CPU that also hosted some memory cache levels.

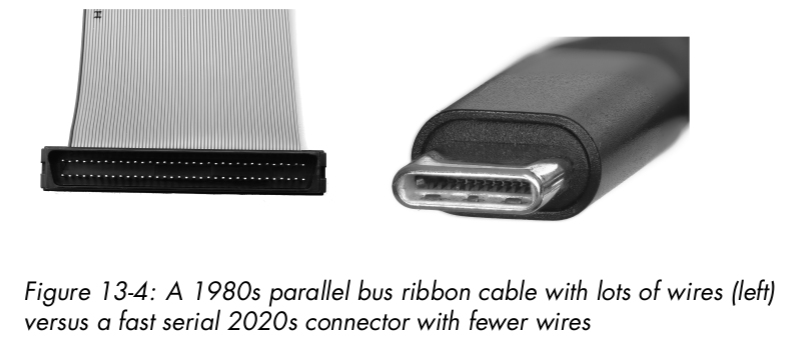

SATA, SSA-SCSI, USB, and CAN are all serial buses.

This change was prompted by technical problems with parallel buses that arrived once speeds exceeded around 1Gbps. Small differences in delays on out-of-box parallel wires can put signals on different wires out of sync, and resynchronizing their data is very hard.

CSI and SATA are competing buses for mass storage devices (for example, hard disks). The Small Computer System Interface (SCSI, pronounced “scuzzy”) is a very ancient, classic, well-tested, reliable, and expensive standard, dating from the 1980s. It pioneered moving compute work for I/O control from CPU into digital logic in the I/O module, freeing up the CPU to work on other tasks more quickly. It’s used today in servers.

The Universal Serial “Bus” (USB) is the one you’re probably most familiar with. However, USB isn’t a bus at all—it’s not even a mesh network. It’s actually a point-to-point connector, intended to upgrade the older serial port.

A USB cable has four wires, two for sending a serial signal and two for power. There are 5 V and a ground in there, so, for example, you can use the same USB cable to charge your mobile phone and exchange data with it.

Smart Architectures

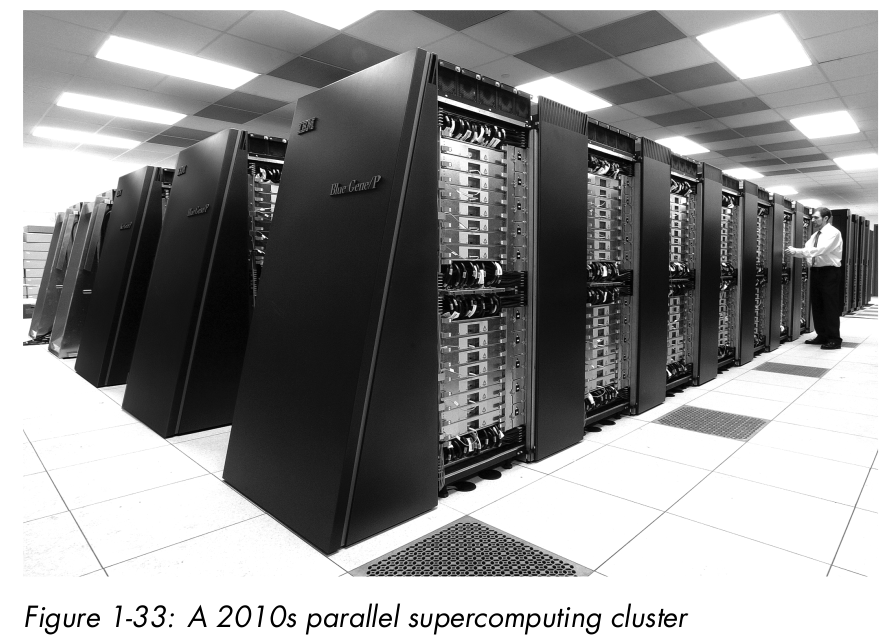

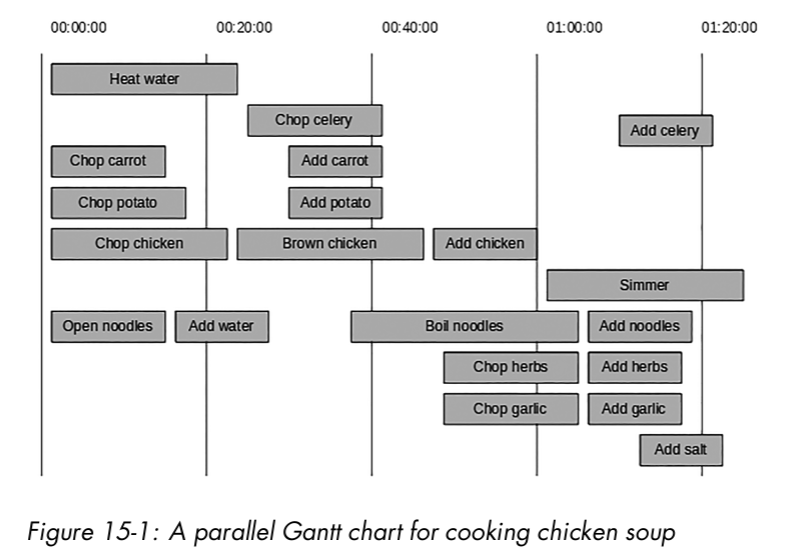

Paralle Architectures

Future Architectures

The speed of electric current is different from the speed of electrons themselves; current usually flows with each electron only moving a small distance, pushing the next electron forward in the circuit. Electrons moving through wire are in a complex environment with many collisions as they bump around,

backward and forward, in random walks. The speed of individual electrons drifting along wire is thus very slow, around 1 meter per hour, while the speed of the current in copper wire can be around 90 percent of the speed of light in a vacuum. Thus, a naive expectation that light will compute much faster than electrons seems overly optimistic; switching over our entire hardware technology for just a 10 percent speedup, from 90 percent to 100 percent of light speed, seems not so useful.

DNA (deoxyribonucleic acid) is the “source code” for life on Earth. In cellular organisms, every cell contains a complete copy of the whole organism’s code (genome) in a set of large double-helix molecules (chromosomes) inside the cell nucleus.v

DNA technology used to be expensive; for example, it took $100 million to sequence the first human genome in 2001. But it has recently rapidly fallen in price, reaching $1,000 in 2015 and $100 in 2023.

The following is not a correct presentation of quantum mechanics and is intended only as a cartoon to introduce some key concepts.

Suppose that objects in the world don’t just exist in a single state at a time. For example, a cat inside a box may at the same time be both standing up, being alive, and also lying down, being dead. This famous example is known as the superposed cat. Suppose that the cat is locked inside the boxalong with a piece of radioactive material. Radioactive material decays completely at random: its behavior can’t be predicted in any way. A radiation decay detector is placed next to it, and connects to a mechanism that releases poison gas into the box, killing the cat if radiation is detected and leaving it alive if not.

This idea, first proposed by Richard Feynman in 1988, is the beginning of quantum computing.

Consider the superposed cat. We could use the cat’s aliveness and deadness as a 1-bit data representation via the encoding dead = 0 and alive = 1.

Call this a qubit, for quantum bit. We could then build an N-bit register by placing N of these cats-in-boxes in a row, to store words, as in a classical register based on flip-flops. Until we open the boxes in the register, there are multiple realities in which the cats inside them are alive and dead. When we open them, we see just one version of reality and that becomes the reality we experience ourselves.

Our best current theory of physics, the Standard Model, is based on quantum field theory (QFT), which combines quantum mechanics with special (but not general) relativity to model reality as comprising a set of fields that each cover space and interact with one another. Each field corresponds roughly to one type of particle, and as in basic quantum mechanics, its amplitudes are those of finding a particle there if we look for it. Unlike basic quantum mechanics, the fields are also able to represent probabilities of finding multiple particles at locations, and it’s possible for these particles to interact and transform into one another in various ways.

QFT isn’t a complete theory of physics, because it omits gravity, which is instead modeled by Einstein’s general relativity (GR). GR is incompatible with QFT because, unlike QFT, it allows space and time to change shape, bending around mass. We rely on relativistic engineering every day—for example, for time correction among GPS satellites, to correct for warping of telescope images, and to correct paths for missions to Mars and elsewhere.

QFT and GR famously don’t fit together, so we have no working “Grand Unified Theory” (GUT) to explain the structure of reality. Current attempts include “string theory/M-theory,” “loop quantum gravity,” and “twistor theory,” but none actually work yet. Some of these theories postulate the existence of extra dimensions.